I believe in softcore pornography… but isn’t that for straight dudes?

Part One: The Discourse, erotic thriller nostalgia, and the feminist angles

For the past two years, give or take, I’ve been formulating and untangling a whole mess of interrelated thoughts on the State of the Sex Scene in mainstream film and television. (This is a manifesto of sorts, so I will be unnecessarily capitalizing phrases to make them seem important. I read enough manifestos while getting my art history degrees to know that unnecessary capitalization is a key component of manifesto writing.) I’m not alone in this preoccupation, by any means. If you, like me, are addicted to the Dying Bird App, then you know that on Film Twitter, we’ve been arguing about the State of the Sex Scene for what seems like a thousand years.

On Film Twitter, it’s well known that there are certain subjects one can tweet about that will increase one’s chances of virality via a flurry of hate-shares and quote tweet dunks. (Anyone who posts anything about Martin Scorsese and the MCU in the same sentence knows exactly what they’re doing.) For a while, one such recurring Discourse was the necessity of sex scenes in movies. For the uninitiated, this Discourse amounted to a different random account going viral every month or so for tweeting some variation of “sex scenes are unnecessary in movies because they don’t advance the plot.” This would prompt a wave of responses along the lines of:

“What are you mad about, there is virtually no sex in mainstream Hollywood movies any more”

“Disney/Marvel killed the sex scene”

“Why is Gen Z trying to revive the Hays Code”

“All the sex is on TV now”

“There should be MORE sex in movies!!”

And so on and so forth. In 2021, after several rounds of the Sex-In-Movies Discourse, something started to give. The Discourse had reached critical mass by the middle of the summer (see, for example, Brianna Zigler’s feature on La Piscine, which had a surprisingly successful revival run at Film Forum in New York, for Paste Magazine). As film critics started routinely championing the Sex Scene, the conversation shifted. It’s not just that Sex Scenes have disappeared from the multiplex, critics and Sex Scene Defenders noted. We all started asking the same questions: What happened to Films for Adults? (Films for Adults are not to be confused with Adult Films—here we encounter our first “softcore/hardcore” distinction, although I don’t necessarily mean this in the traditional “no penetration/penetration” sense.) What happened to the Good Old Days, when Hollywood released films about sex, films that blatantly aimed to arouse while still telling an engaging story? What happened to mainstream erotic cinema?

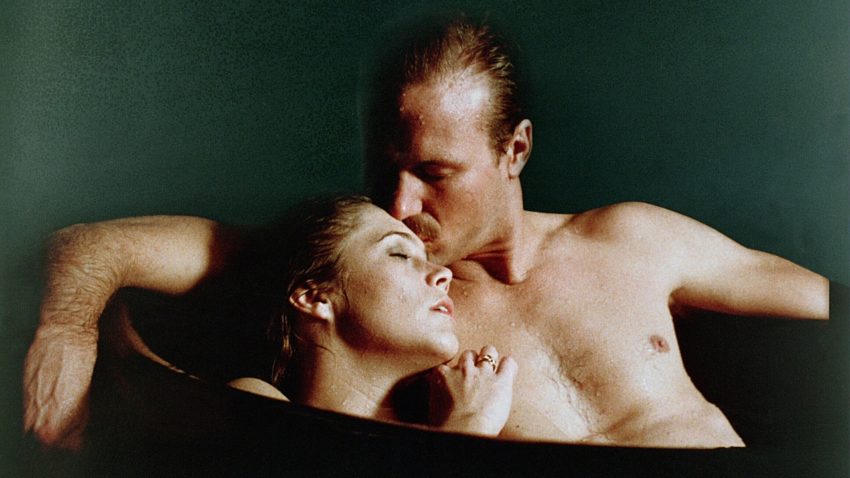

One genre floated to the surface as an object of collective fascination and nostalgia: the erotic thriller, perhaps the high water mark in terms of Hollywood’s permissiveness of sex on screen. In July, the Criterion Channel unveiled a neo-noir collection that proved quite popular in the context of the Discourse. The collection included Lawrence Kasdan’s Body Heat (1981) and Brian De Palma’s Body Double (1984), both often cited as important precursors to the classic erotic thrillers of the late ‘80s and early ‘90s.* That same month, cinephile cult favorite journal Bright Wall/Dark Room devoted an issue to the erotic thriller. In the spring of 2022, king of the erotic thriller Adrian Lyne returned with a new entry into the genre: Deep Water, starring Ben Affleck and Ana de Armas. This new release prompted yet another wave of erotic thriller appreciation (If not appreciation for Lyne’s new film), including an Erotic Thriller Week at Vulture.

This borderline fetishization of the erotic thriller, however, potentially reveals the limitations of a previous era’s idea of what’s Acceptably Titillating. For one thing, many of these mainstream erotic films prioritize the titillation of straight, male viewers. This is not to say that other viewers can’t find something to excite them in these movies—many do, including myself. I firmly believe that one can legitimately enjoy art that’s “not made for you,” but we can’t pretend that the erotic films of the 80s and 90s don’t have a legacy of sexism (and homophobia) on and off screen.

In the spring of 2022, Karina Longworth released the “Erotic 80s” season of her Hollywood history podcast You Must Remember This. Longworth approaches the era, when Hollywood was making films that took sex seriously and showed that sex on screen, through a consistently feminist lens.** While Longworth mourns the loss of a time when Hollywood made Films for Adults, she also critically examines the deeply conservative ideas about gender and sex that underpin many of these films, as well as the oftentimes terrible treatment on set and off of the actresses who starred in them.

Longworth, a historian through and through, endeavors primarily to bring the past into focus; but she implicitly makes the argument that any hypothetical mainstream erotic cinema of the 2020s can’t and shouldn’t look exactly like it did in the 1980s. In a 2021 trend piece called “Why Hollywood is shunning sex,” Christina Newland explores the possible reasons for the decline in erotic content in mainstream Hollywood films. Among other things, Newland theorizes that “this new discomfort with depicting sex” is likely tied to the #MeToo movement and the film industry’s ongoing reckoning with systemic sexual abuse. She writes:

The reckoning … in the film industry has ushered in enormous positive change, encouraged filmmakers to nix female objectification, and led to the increasing introduction of intimacy coordinators to help actors feel safe. Their efforts ensure issues of boundaries and consent are correctly navigated while filming sex scenes. But even then, anxieties remain about the validity of depicting sex, and whether it is gratuitous or not. Lately, sex has felt like a very serious topic; one that no one wants to joke about or “get wrong.” Filmmakers may be responding to this anxiety with their own shyness around the topic: no one wants a social media storm on their hands.

These critiques of the mainstream erotic cinema of yore, and the desire to avoid repeating the harms of the past, must be taken into consideration during any discussion on the topic. I’m not interested in Romanticizing the 1970s or 80s or 90s or whatever. I will always love old films, and I believe that art from the past often remains relevant to contemporary life; but I live in 2023, for better or for worse. And instead of bemoaning how They Don’t Make ‘Em Like They Used To (although I do, also, do my fair share of that), I’d like to see a New Mainstream Erotic Cinema—one that embraces a wider idea of what’s sexy and who deserves pleasure. We’re still here, we’re still having sex, and we still want hot movies about it.

In arguing for the value of erotic content in the mainstream, I often feel like Crash Davis (Kevin Costner) making his famous speech in Bull Durham (1988).*** Annie Savoy (Susan Sarandon) asks Crash what he believes in when it comes to matters of the heart, and he proudly declares, amidst a litany of other things, that he “believe[s] in softcore pornography.” And I think that about sums it up for me, too. I believe in softcore pornography, and I believe in softcore for all who want it.

When I say “softcore pornography,” I don’t necessarily mean actual softcore porn, although I’m pro that, too. I use this term self-consciously, as “softcore” is often used as an epithet when dismissing or negatively judging the type of mainstream erotic content for which I’m advocating. One of the weirdest retorts the Anti-Sex Scene Tweeters throw out to the Sex Scene Defenders is that people who want to watch Sex Scenes should just watch porn. There is a distinction between mainstream erotic content and pornography, even if blurring the lines is sometimes fun. (I try not to be a binary thinker.)

For the purposes of this manifesto, “softcore” isn’t a category of porn based on heteronormative ideas about penetration being the ultimate sex act. No, I use “softcore porn” to evoke an attitude, a vibe. I’m talking about films and television that revolve around sex, include fairly explicit Sex Scenes, and exist to sexually excite the viewer on some level. This wide net can catch anything from a raunchy rom com to, yes, an erotic thriller.

Why do I believe in softcore? Well, for starters, it can be fun. In a media landscape saturated with Escapist Content—and I use “content” derogatorily here—why the sheepishness about a little sexual fantasy? Watching beautiful people in compromising positions on screen makes me happy, so sue me. When confronted, some Sex Scene Defenders will hedge, saying that it’s not about actually seeing the sex. They miss sensuality and chemistry and heat in Hollywood films—the suggestive charge and the promise of adult activities. While I agree with all of those things, I must clarify that I also want to see the sex. Watching a film is always, to some degree, a voyeuristic act, and I’m a cinephile. Of course I like to watch. So do a lot of people, it’s not that weird.

Beyond personal indulgence, I do believe in the power of softcore to destigmatize certain kinds of sex. Mainstream erotic content reflects and, to some extent, shapes sexual mores. It can push the boundaries of The Norm. Now, hey, more power to you if you have no desire to see your sexual preferences and practices “normalized.” But, to me, there’s something insidious about the way mainstream erotic content has evaporated onscreen as society has become more sexually permissive offscreen. Perhaps it’s respectability politics, but I think it’s simpler than that.

It’s clear that there are Unspoken Rules about what kind of erotic images and scenarios Hollywood deems on the Right Side of Explicit. This comes up occasionally when a film hits trouble with the MPAA, particularly when filmmakers are desperately trying to avoid or appeal an NC-17 rating. Here’s the deal: I’d wager that more people than not consider any erotic imagery that’s not focused on a straight dude’s pleasure (onscreen and/or off) to be “more explicit”—even if the actual level of explicitness is objectively the same. I don’t think most people even do this consciously, but it’s indicative of widespread assumptions about what kinds of sex count as softcore (and therefore okay for mass consumption) and whose pleasure is prioritized.****

We’ve all kind of collectively agreed that just making softcore for straight dudes isn’t going to cut it anymore. But how, exactly, does one make softcore for other gazes when the Unspoken Rules about what counts as softcore actively undercut that whole idea? I would contend that Hollywood has, by and large, been all-too-content to cease making mainstream erotic cinema altogether in order to avoid challenging the Unspoken Rules.

The Unspoken Rules, as far as I can distill them down, are these:

-

- Sex acts that prioritize female pleasure (or the visual framing of any sex act that prioritizes depicting female orgasm) can never be softcore. I think this is the Unspoken Rule that’s gotten the heaviest beating over the last decade or so, even as I hesitate to say it’s finally been discarded. Cunnilingus, specifically, has become quite the popular addition to the R-rated Sex Scene repertoire. I’m not saying this is completely thanks to Ryan Gosling, but… he’s not not responsible.

- Queer or non-heterosexual sex scenes can never be softcore. This is a huge one, especially when we’re talking about gay sex scenes between men. See:

- Male full-frontal is the end all be all of nudity (the final “front”-ier, if you will), and an erect penis can never be softcore. I think we’ve seen some pushback on the penis part, but not the erect part. But I’m sorry to report that the floppy prosthetic dicks on HBO are doing nothing for the Agenda.

Now, I’m a self-professed Horny Bitch who desires men. Naturally, then, I’m most sensitive to the attempts Hollywood has made at catering to Female Desire (a term which is always, always straight and cis-coded). And I will concede that, of all the demographics historically un-catered to by mainstream erotic film, the Lusty Straight Ladies™ have made the biggest strides over the last twenty years.

And, indeed, as you have read this manifesto, you might have been thinking, “Leah, hasn’t there been plenty of Sexy Stuff for the Lusty Straight Ladies lately? Isn’t objectifying men cool now? Haven’t the thirsty fangirls won the war? Didn’t you just watch Alexander Skarsgård on a leash in a suburban AMC? And didn’t Magic Mike let those Hollywood execs know that catering to Female Desire is profitable a whole damn decade ago?”

To this I say, “Well… sort of.” If you look at most of the films aimed at satisfying Female Desire, so many of them are simply not horny. It’s 2023, and I still struggle to think of a better straightforward celebration of a lady’s Horny Rights than Shakespeare in Love, which came out in 1998. (That’s not an invitation to list movies in the comments. I’m sure there are examples, but the fact that I can’t think of any off of the top of my head proves my point.) And let’s talk about the epidemic of leading men who will play the sex symbol off screen but hesitate to do anything remotely sexy in their art. I don’t think Female Desire is taken much more seriously in Hollywood as an actual sexual concept than it was 25 years ago.

There’s lip service given to the idea of providing women with “what they want,” but what Hollywood says women want is rarely sex. And I, the self-professed Horny Bitch, take extreme issue with that. Where is the softcore for the Lusty Straight Ladies?

Coming soon, part two: “I believe in softcore pornography… but that’s not what Channing Tatum says I want.”

*Both films are sometimes categorized as erotic thrillers in their own right, but the generally accepted narrative of the erotic thriller’s brief heyday pins the genre’s explosion in popularity on the success of Fatal Attraction in 1987.

**Longworth does periodically engage with and critique the aggressive heterosexuality of the period, especially in Part 3 (“1980: Richard Gere and American Gigolo”) and Part 8 (“1985: Fear Sex, Jagged Edge & AIDS”). But I would still argue that, by and large, “Erotic 80s” is a feminist project more than anything else.

***If you listened to “Erotic 80s,” then you might have guessed that I watched Bull Durham for the first time at Karina Longworth’s suggestion.

****I’m going off of anecdotal and experiential evidence here. Sometimes I find myself (naively, perhaps) shocked by the entrenched social conservatism I encounter when I leave my Bubble, and I don’t have to stray very far. Additionally (I’ll say it here in the footnotes like a coward), everybody has implicit biases, and dismantling them is a daily practice.