Master and Commander: The Far Side of the World released in the fall of 2003, at the height of Russell Crowe’s stardom. The film, based on a long-running series of novels by Patrick O’Brian, had franchise potential and a subtitle that promised sequels. Despite a strongly positive critical reception, the movie famously could not attract enough people to the multiplex to make a profit against its generous $150 million budget. The film earned ten Oscar nods, including for Best Picture, but The Lord of the Rings: Return of the King swept the competition at the ceremony.* Having gotten neither the box office receipts nor the awards hardware to justify a sequel, Master and Commander faded into collective memory as a particular kind of middling prestige picture and a failed franchise starter.

Seventeen years later, Peter Weir’s naval epic has its small share of passionate fans who will sing its praises whenever given the opportunity. It would be fair to say, though, that Master and Commander now has a bit of a reputation as a Dad Movie. It’s generally remembered as a solid war film made with impeccable attention to historical detail, even if the specific characters and events depicted are fictional. I’m not here to argue that the film isn’t a Dad Movie, because that would be disingenuous; however, inclusion in the Dad Movie hall of fame does not automatically disqualify the film from consideration as a truly great work. Master and Commander is the best kind of Dad Movie, and the film deserves a broader appreciation.

As the marquee star and the leading man, the film’s marketing positioned Russell Crowe front and center. Crowe, at the time relatively fresh off of three consecutive Oscar nominations for Best Actor and considered a bankable headliner, received a reported $20 million salary up front for the picture. Although he’s continued to work steadily in Hollywood, many accounts of Crowe’s career mark the misstep of Master and Commander (in conjunction with increasing reports of his violent outbursts offscreen) as the beginning of the end of his superstardom. Given this context, reevaluating the film’s place in Crowe’s filmography becomes an excellent place to begin a larger reevaluation of the film’s reputation.

If Master and Commander is a generally underrated film, then it follows that Captain Jack Aubrey never ranked as one of Russell Crowe’s iconic roles. But for those of us who love the movie, Crowe’s magnificent lead performance stands out as one of the best of his career. The actor’s charisma and gravitas have never been put to better use on screen. Crowe gives a lived-in performance that feels effortless; he anchors the film, but he never seems to be working for your attention.

Crowe’s ultra-masculine screen persona has frequently led Hollywood to cast him as men capable of great violence. His imposing physique, coupled with his intense demeanor, lends credibility to his portrayals of brutality. Whether a Crowe character registers as a hero, villain, or antihero often comes down to how the film frames that capacity for violence. Captain Aubrey is of a piece with the rest of Crowe’s decidedly masculine characters; the role is not a pivot or a play against type. But Captain Aubrey epitomizes a masculine ideal rather than the toxic masculinity so often at the root of Crowe’s characters. (Remember, this is a Dad Movie!) As a successful military man, the violence Aubrey enacts is ritualized, justified, and honorable. It is controlled to the utmost degree by both military norms and the captain’s own rigid moral code. The Napoleonic wartime setting rationalizes the necessity of the violence in the film, as the killing occurs in the service of an imagined greater good.

Besides his facility with a bayonet, Aubrey displays another key trait of idealized masculinity: leadership. As Scott Tobias wrote last year in his superb “Revisiting Hours” piece on Master and Commander for Rolling Stone, the film works particularly well “as a study in leadership.”** The film takes a keen interest in what it means for Aubrey to be a worthy leader, and Crowe’s acting choices perfectly complement this thread of the film. Crowe possesses a natural charisma that provides authenticity to his portrait of a respected commander, but he doesn’t coast on this alone. He brings a three-dimensionality to Aubrey by subtly modulating his behavior depending on what image the captain needs to project in any given situation. Crowe reminds us that leadership is an act in both senses of the word—an action and a show. He communicates the way that Aubrey constantly performs leadership without drawing undue attention to his own performance as an actor.

Crowe’s work in the film stands out as some of the most delicate and nuanced acting in his oeuvre. Yes, he delivers stirring speeches with aplomb. (“England is under threat of invasion, and though we be on the far side of the world, this ship is our home. This ship is England,” Aubrey intones to his crew in a particularly rousing moment before the film’s climactic battle sequence.) He fixes his trademark Russell Crowe squint on the horizon as he watches for the enemy ship that Aubrey has been tasked with capturing. Aubrey is, to a degree, another one of Crowe’s serious men. As captain, Aubrey assumes responsibility for everyone on the ship and must bear the burden when men under his command die. But he also cracks jokes—one dinner scene in the captain’s cabin ends with a memorably bad pun about “the lesser of two weevils”—, mentors the younger crewmates, and generally tries to make all of his men feel needed on the ship. Crowe brings an attractive warmth to Aubrey, a quality that rarely shines through in the actor’s other roles. It isn’t all glowering from the deck; leadership also looks like forming honest connections and making people feel special. Crowe takes an understated approach, and this light touch belies the intentionality and thoughtfulness of the performance.

Master and Commander undoubtedly provides a window into an exclusively masculine world. Women are barely alluded to visually or verbally; men comprise the bounded universe of the HMS Surprise. In addition to the military hierarchy of power codified and enforced by the British Royal Navy, a network of homosocial relationships defines life onboard the ship. These relationships are largely positive and entirely platonic; the crew members mostly support each other, with one tragic exception. This isn’t a film about problematic or alienated masculinity. As one would expect of a Dad Movie classic, Master and Commander mostly posits that men are alright.

The film does not completely gloss over the more unpleasant or even traumatic aspects of British naval service in the Napoleonic Wars. An adolescent midshipman undergoes an arm amputation early in the film; one character offhandedly mentions the practice of impressment, reminding the viewer that some of the men on the ship are likely there involuntarily; and several members of the crew who we have gotten to know rather well are dead by the end of the movie. But the crew members make a home for themselves on the ship, and life there isn’t unbearable. They make friends, they make do. Weir’s film suggests that there is something redemptive, something powerful, about male camaraderie. While this theme isn’t at all unusual for a war film, Master and Commander is especially compelling for the way it treats this idea as more than a truism.

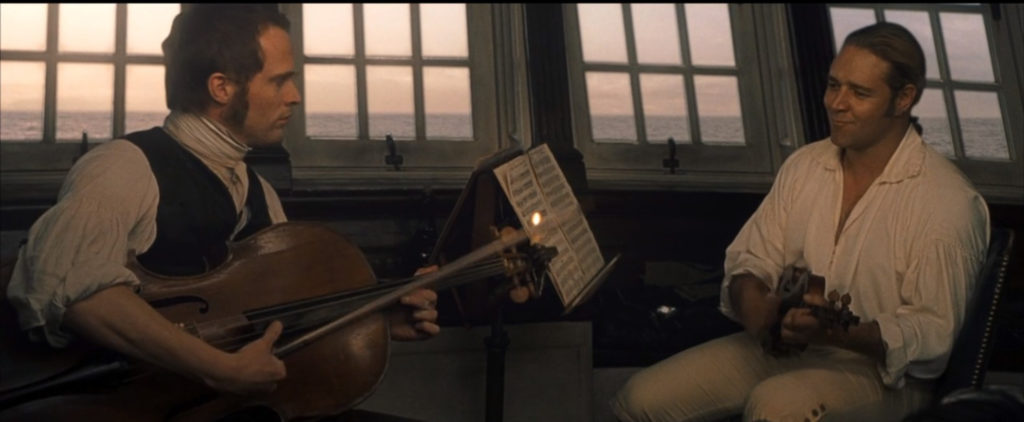

The film takes male homosociality as one of its main subjects, and so, fittingly, the close friendship between Captain Aubrey and Dr. Maturin (an also excellent Paul Bettany) serves as the film’s center.*** Aubrey technically outranks Maturin, so it’s not truly a relationship of equals; but Aubrey treats Maturin as a confidant and sometime advisor. Aubrey and Maturin seem to hold each other in genuine high regard, and their mutual respect forms the foundation of their relationship. In fact, these two men respect each other enough to remain friends even as they almost constantly disagree with one another. Their opposing approaches to life lay out the final thematic preoccupation of the film.

I love Master and Commander most of all for the way that it captures the rhythm of pursuit. On the one hand, Master and Commander is literally about the thrill of the chase—the HMS Surprise follows the French privateer Acheron for the entirety of the film’s runtime. Aubrey has orders to engage the Acheron and hopefully take her; what little plot the movie has revolves around this objective. Weir mounts three battles between HMS Surprise and the Acheron, and each encounter thrills in its own distinct way. Watching Aubrey and his men outwit the superior French ship through various clever means proves to be an undeniable pleasure. Most of the film’s budget went into the action set pieces, and the practical effects on display are spectacular.

But the movie spends just as much time with the crew during the downtime between battles, providing a glimpse into everyday life on the ship. The texture of the film comes from this contrast between the action and the waiting, the forward momentum of the hunt and the stillness of the quiet points when action is impossible. Captain Aubrey and Dr. Maturin each embody one of these two states, to a certain degree. Aubrey always wants to push onward and take every opportunity for a fight that presents itself. He’s driven by duty and motivated by the thought of glory. Maturin thrives in the cessations, enjoying the moments when he can indulge his interests as a naturalist. He sees stalking the Acheron beyond what was explicitly ordered as a doomed exercise, and he repeatedly asks Aubrey to consider giving up on taking the enemy ship.

Aubrey’s desire to unceasingly chase the next goal exists in tension with Maturin’s wish to stand still and find contentment in the observable present; the way that the film doesn’t resolve this tension only strengthens the metaphor. Master and Commander never exactly comes down on the side of one man or the other. The film presents both men as reasonable, capable, and intelligent. Aubrey and Maturin each willingly concede their point to the other at different junctures of the film. We experience the gratification of a successful maneuver against the Acheron, but we also see the human cost of Aubrey’s refusal to call it a job done and leave the Acheron alone. The film makes us privy to the small joys among the crew during the pauses in fighting, but we’re also made to understand how an inability to go after a common objective can lead to discontent and unrest among the men. The film depicts this push and pull with an unusual clarity, resulting in a work that perfectly reflects the core truth of how it feels trying to balance ambition and fulfilment in one’s own life. Seen through this lens, the open ending of the film turns out to be rather perfect. There is no single achievement the attainment of which will satisfy the ambitious person. The pursuit is incessant.

The purity of this metaphor cannot be separated from the masculine milieu of the film. The drive to make one’s name, to leave some mark of one’s existence in a public way, has historically been coded as masculine in the Western tradition. Concepts of gender essentialism used to keep the status quo reinforce the idea that women aren’t naturally ambitious. Films about women’s ambition necessarily have to grapple with (or can be biased by) that complicated reality. On film, as in life, ambitious women face different treatment than ambitious men. Because ambition is often assumed to be an unquestioned positive value for men to possess, Master and Commander can more easily extrapolate its argument to the realm of the abstract.

As a film that deals with ideal masculinity, Master and Commander works so well precisely because of its Dad Movie tendencies. The movie presents an aspirational and positive, but not sugar-coated, vision of what it means to be an admirable man. Russell Crowe’s casting and performance are so perfect here because the actor trades in on his “masculine” reputation to create a paragon in Captain Aubrey. The film posits that these masculine ideals are valuable in and of themselves, in isolation. By sidestepping the subject of women almost entirely, the film never puts its masculine ideals into any oppositional, binary configuration with feminine ideals. Although the film shows a solely male domain, the movie never implies that only men can achieve these ideals. Like the true Dad Movie that it is, Master and Commander instead envisions these positive aspects of masculinity (like good leadership, camaraderie through hardship, and healthy ambition) as universally good values applicable to anyone on the gender spectrum. If you’ve written off Master and Commander as “just a Dad Movie,” it’s worth a second look. The film’s Dad Movie-ness is actually its secret strength.

*Master and Commander won two Academy Awards, for Best Cinematography and Best Sound Editing. These were the only two categories in which Master and Commander did not compete against Return of the King, which won all eleven awards for which it was nominated (and which still holds the record for highest clean sweep at the Oscars).

**This piece convinced me to revisit Master and Commander myself. Prior to last year, I had not seen the film since I was a preteen. Tobias’s framing of Weir’s film as the anti-Pirates of the Caribbean made me laugh; when I first watched Master and Commander, I disliked it essentially because it wasn’t Pirates, with which I was obsessed at the time.

***While I’m sure someone has written Aubrey/Maturin fanfic and published it somewhere on the internet, there’s no textual evidence in the film that Aubrey and Maturin are more than friends to each other. I would also argue that Crowe and Bettany don’t have enough sexual chemistry to support a ship. (No pun intended.)